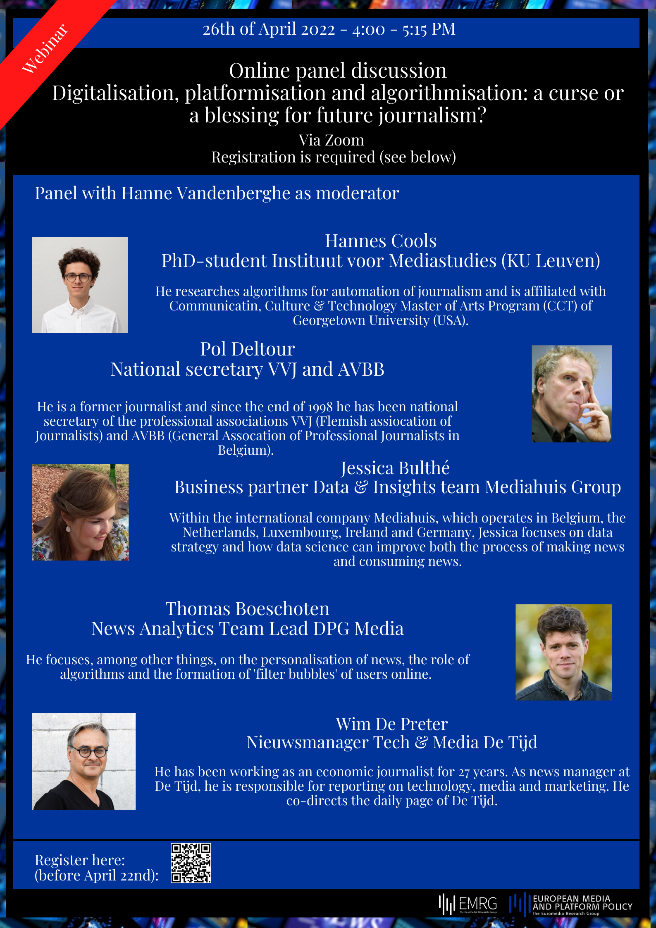

National workshop - Belgium

Digitalisation, platformisation and algorithmisation: a curse or a blessing for future journalism?

National workshop of the Jean Monnet Network on European Media and Platform Policies (EuromediApp)

26 April 2022

Venue: online

Program

A first main insight of this conversation, is that the platformisation of news media was seen as an important opportunity for traditional news players such as newspapers to reach a bigger audience. There are more options to ensure people get in contact with the content you make. In former times, newspapers for instance had only the shop window of the newspaper stores to sell their products, but via the international platforms such as Facebook or Instagram this window is very much enlarged. However, these platforms are for these traditional news brands only relevant as a first contact point; their main goal is to guide the audience to their own platforms and websites. This has a twofold reason, first and foremost it is crucial for their business model to make it possible that the audience pay for their content and secondly, it was argued by the data specialist of Mediahuis as an important aspect in a democratic society because, as we all know, research indicates that the audience have little trust in news via social media, so the provision of information via established news brands gives a guarantee that the audience will trust the news they consume.

A major challenge in this story is, how far established news brands are willing to go to attract the attention of young people? The challenge is to deliver simple and accurate news via social media channels as a way of introducing these young people to established news brands, in the hope they are willing to pay for news when they have grown older. However, the pitfall is how ‘simple’ can you formulate the news without losing your relevance and accuracy? For instance, the Instagram page NWS NWS NWS of the Flemish public broadcaster, specifically targeting the young audience, do not bring political news that is so-called ‘too institutional’. And also articles of the Mediahuis newspapers are summarised at their Instagram page in a few sentences, which makes it hardly to be called a ‘news article’, which results in the fact that journalists often fail to recognise their own articles on these Instagram pages. Another striking trend in personalisation is the podcast phenomenon: podcasts have been made on just about every subject, aimed at every taste. Yet some expert panelists say they do not see this multitude of offerings as personalisation. It should rather be seen as segmentation rather than personalisation.

A second challenge in the use of platforms, is the so-called filter bubbles, which is both defined as people getting only a specific type of news, and getting news only via one or a limited set of news sources. The panel lists agreed that traditional news media play a key responsibility in which type of content they push to Facebook or other social media platforms. There is need for a balance between clickbaits or articles only published to attract an audience, articles that fit within one’s own news brand and articles that are socially relevant. However, filter bubbles are not seen as a significant danger in the European context because news brands has made an important choice to not personalize homepages, which is the case by for instance the Washington Post where someone who is not interested in political news will not get election results on his or her home page. In Europe, the main news companies have made the choice to see a homepage online as an equivalent of a homepage of a printed newspaper from 15 years ago: editors who make a selection of the socially relevant articles at that very moment, that is similar for every single user, regardless of the region he or she lives in or his or her news interests. Personalised news is only seen as a practical tool for hyper-regional news, such as a fait divers that a cat that is stuck in a tree. European news media are not financially dependent on page views, but have a subscription-based business model, which is seen as the most important condition to make independent journalism.

Another issue that was raised, was the way metrics or data are used in newsrooms. The main indicated pitfalls according to the panel are: using data to evaluate articles as good because they have reached a larger audience; and use data to decide which kind of articles that should be written. However, Mediahuis and DPG Media, the two major commercial companies in Flanders, clearly opt for a so-called data-informed system: using data to inform journalists and editors-in-chief, and not as a data-driven system: using data to make automatically content-related choices. The editorial freedom is paramount. The data specialists could even not imagine that editors-in-chief would accept any suggestion on content-related decisions based on their data.

Before I wrap up, there is the striking observation that algorithms are not yet used in the Flemish newsrooms at this moment. Recommendation software to help select news is for instance not used and not all panel lists were familiar with this kind of software. While some news outlets in the Netherlands using robot journalism for several years both as a content moderation tool at a reaction platform and as an automatic tool to generate local news based on datasets, this is not used in the Flemish newsrooms, although there are ongoing experiments. Robotic journalism is evaluated as useful in some cases, such as to provide sport results or stock market figures. Journalists can then spend the time more usefully, on long journalism for example. Socially relevant articles will never be made by a robot, according to the panelists.

To conclude, a main issue in this debate is that data need to be used as an information tool, a data-driven system is not desirable. At the end of the day, neither data specialists nor the audience are in a position to determine which news stories should be written or in what way, this is the responsibility of newsrooms and their editors and editors-in-chief.

Take-aways

Are metrics a curse or a blessing?

The big difference lies in the extent to which data is leading: namely, is it data-driven or data-informed journalism?

Journalists would not allow data-driven journalism: they have too great a sense of social responsibility and also want to retain their journalistic freedom.

Putting the responsibility to social media platforms as enshrined in the Digital Services Act is fine, but sanctioning professional group ethics-based news media is wrong.

There has been a lot of investment in technology over the last decade, but now it is high time to invest in journalists again. AI can help with carrying out research faster, with transcriptions for interviews, translation, etc.

Journalistic integrity is crucial. Journalists set the direction, this is the journalistic DNA that is cultivated in journalism training. This journalistic DNA should be support and nurtured in every media company.